Memorial Day commemorates the sacrifices of service members. According to the National Cemetery Administration, it began after Major General Logan issued the ‘Memorial Day Act’ in 1866 to remember fallen soldiers after the American Civil War and a day to decorate their memorials with flowers and other mementos.

However, this day has started including those who haven’t served in the military. Many communities use this day to visit graves of their loved ones.

Why do we use plants to honor the dead?

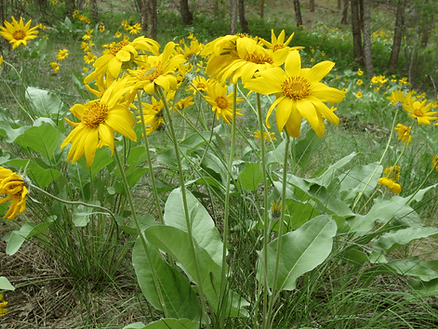

Many plants follow the same seasons, literally and metaphorically, as humans: we’re born, we live, we rest, we may have offspring, we hold roles in our communities, we pass away.

In the spring, we awake after a long, cold winter. In the summer, we grow–reaching peak fullness in early autumn when we return to deep rest in the winter. While each part of the world varies, we can affirm that this cycle has existed for all life for time immemorial.

All of our lives are tied to the green world around us. It’s a natural thing to live a life and honor that experience through the beings that are always near us, bringing childlike joy and wonder to everyday living, including the end of our loved ones lives.

Why are trees so popular as memorials?

Trees are arguably one, if not the most, ‘charismatic megaflora’ on Earth. In other words, beings that are so impressive to the naked eye that it provokes an emotional reaction; we physically look up to them and frequently care for them as family members.

Long-lived species like oaks offer a way to commune with our loved ones long after their passing. Trees give protection from harsh rays, cool our homes, live for many human generations, provide food and shelter for innumerable species, serve as a keystone connection to ecological habitat and are a constant physical reminder honoring those that have passed.

Humans & Trees

Humans and trees are more alike than folks may realize. While physically, we may differ, we have been in relationship with our tall, woody friends for a very long time.

One could say that we heal trauma and damage similarly through compartmentalization that occurs faster near new growth, and find resilience in where we are planted.

All trees may have similar forms and structure (in the sense that they have secondary growth as woody material), but not all species of trees are directly related to each other or even have common ancestors. This is a scientific phenomenon called convergent evolution.

How incredible is it that that so many different beings that have differ in community roles end up sharing similar traits even though they aren’t ‘actually’ related? It kind of sounds human, doesn’t it?

How do I choose a tree as a memorial?

This can be a hard question as it becomes more complicated depending on exactly the answer you’re looking for.

We can separate the following advice into three different categories for the folks that will be assisting you during this difficult time: your arborist, the funeral director and a spiritual advisor/clergy. All of these experts should be in conversation with each other and your family.

You can find a Certified Arborist through the Trees Are Good: Find An Arborist search function.

Your arborist should follow the adage: ‘right tree, right place, right reason, right season’. They will likely ask if you have a species, leaf colors, flowering or anything particular in mind that reminds you of the person you have lost.

Your arborist should be trained on how to plant a tree properly, keeping in mind the size, location especially in regards to long term maintenance and should communicate this to you. The US Forest Service provides a great manual for tree owners.

If you’re choosing to inter your relative in a cemetery, talk about tree care and what the tree maintenance schedule looks like with funeral home/cemetery staff. If the trees are not well-maintained, especially over graves and memorials, other important details for your relative’s resting place may be overlooked.

Both deciduous and evergreen trees are suitable, depending on the story the family is trying to tell. It may be wise to ask if the family wants a tree that ‘follows’ the seasons (in the sense that it goes dormant every year) or one that ‘perpetuates’ all of the seasons (that the tree doesn’t enter dormancy in the winter).

This phrasing may not work for you, so feel free to explore how to ask these questions with someone that supports the family during difficult times such as clergy or the funeral director.

Planting saplings can be therapeutic for families that have lost children. As the tree grows and reaches maturity, one can remember that seeds can be shared with friends and relatives to commemorate life events.

Trees are just as unique as people and have characteristics that shine in different seasons:

A native redbud (Cercis occidentalis or Cercis canadensis) which blooms in early spring for a loved one that had a birthday during that time or to celebrate new life after a long winter. The heart shaped leaves that exist throughout the growing season evoke a sense of whimsy and have charismatic movement when the wind blows by.

Perhaps the person who passed away loved water and was creative. If appropriate site conditions exist, a native willow species may be a good option. Many creative opportunities exist with willow, especially within weaving traditions.

Be open to what moves and inspires you.

I lost a tree that means a lot to me. What are my options?

Depending on many factors like the species, health, and existing risk you may be able to support your memorial tree as a ‘snag’.

‘Snags’ are trees that have died, but still exist as habitat. They fill ecological roles beyond their natural life. An excellent online resource for your arborist is Cavity Conservation Initiative.

If the tree is not able to be turned into a snag, you can request to keep burls or other prime pieces of wood for art pieces, furniture, frames for paintings, or other creative expressions.

If all else, you may be able to request to mulch the tree and keep the mulch for your use. or use for firewood. Please remember to keep felled trees on your property. It helps reduce spread of invasive species & diseases.

I’d like to celebrate a tree in my life

Here is a short list of ceremonies to explore. This isn’t a ‘scientific’ list of things you can do to save a tree, but rather a way to come to terms spiritually and emotionally with events that are co-occuring to you and the tree.

When you plant a tree, consider taking photos. You can write letters to the tree and place them on the branches, or bury them in the soil.

Commit to watering your newly planted tree on certain days of the week. After establishment, consider doing deep waterings seasonally.

When you have decided to remove the tree, let the tree know what is happening. Sit with the tree and chat with them. Thank them for anything they’ve helped you with: shade, food, play, etc.

When decline begins, ask the tree to produce seed so you can propagate its progeny. Some trees will produce vast amounts of seed at the end of its life anyway, but it doesn’t hurt to ask.

When you’ve removed a tree, consider building a fire with the felled wood. Try writing letters of good memories and place them in the fire. As the smoke reaches into the sky, so will your thanks. The cooled ashes have many uses and can be reused.